-Rpnunyez, we'd love to hear your story and how you got to where you are today, both personally and as an artist.

Well, it's a long question to answer. It almost makes me go through my whole life.

I have dedicated my whole life to studying hard for my mechanical engineering degree. As soon as I finished my degree, I started working as an engineer for about 18 years. Then, I passed the state exams to become a technology teacher in high school. Finally, I could retire to dedicate myself completely to my passion, which has become my way of life.

On a more personal note, I think it would take me two lifetimes to become what I would like to be. I'm afraid that's impossible, so I have to be satisfied with keeping that goal and going as far as I can. I really believe that it is not a small thing.

Regarding my evolution as a photographer, I started by building my own analog photographic laboratory, and I began to take my first steps as a photographer rather randomly, but I soon discovered the path I wanted to follow, and I have not abandoned it. The turning point was getting to know mainly the work of Marc Riboud, Leonard Freed, Larry Towel, and above all, Wayne Miller.

I was impressed by Marc Riboud's simple composition of his photos and his exquisite treatment of the tonal range of greys.

I love the impeccable and original composition of Leonard Freed's images.

I love Larry Towel's handling of perspective, his impeccable treatment of the range of greys, and the humanist dimension of his projects.

From Wayne Miller, my favorite is the self-confessed humanist dimension of his photos, the emotional strength they convey, and his equally impeccable tonal range.

All of them continue to inspire me with their work, firstly in terms of the purely visual and artistic, but also, and especially, secondly, with their way of understanding the photographic act and, therefore, their way of understanding the world.

As far as I am concerned, I never think of my photographs as art objects or objects of consumption, nor do they have anything to do with ephemerality. I think of them, even before I see them materialized in a project, as tools at the service of an idea as simple as Wayne Miller so masterfully summarized it:

"We can differentiate ourselves by race, color, language, wealth, and politics, But consider what we have in common: dreams, laughter, tears, pride, the comfort of a home, and the desire to love. If I could photograph these universal truths ..."

This simple but deep consideration not only permanently guides how I experience photography but has shaped how I see the world.

-Your statement mentions the importance of eliminating contextual clues in your portraits. What inspired this approach, and how do you achieve it in your work?

The origin of RED BLOOD was none other than a mixture of boredom and annoyance of hearing, over and over again in the mass media, news related to, in quotation marks, migrants.

This word "migrant" has a perverse meaning because, like many others, it influences our way of thinking: it automatically places the human being you are referring to outside your world, turning them into someone alien to you, in short, dehumanizing them.

In a world where Lampedusa, Catania, Puerto de los Cristianos, the Island of Lesbos, and an innumerable list of places are ports of arrival, at the very best, for thousands and thousands of people looking for a better life, it would be great, necessary, and even therapeutic to stop seeing migrants and to see them simply and plainly as human beings.

In a certain sense, the documentary photographer's job is none other than to compose stories where the main character and various visual-social, economic, and geographical clues weave a tapestry of sensations, of emotions, that give voice to that story.

However, these clues, on many occasions, turn against us, forcing a subtle and unconscious prejudice about what we are contemplating.

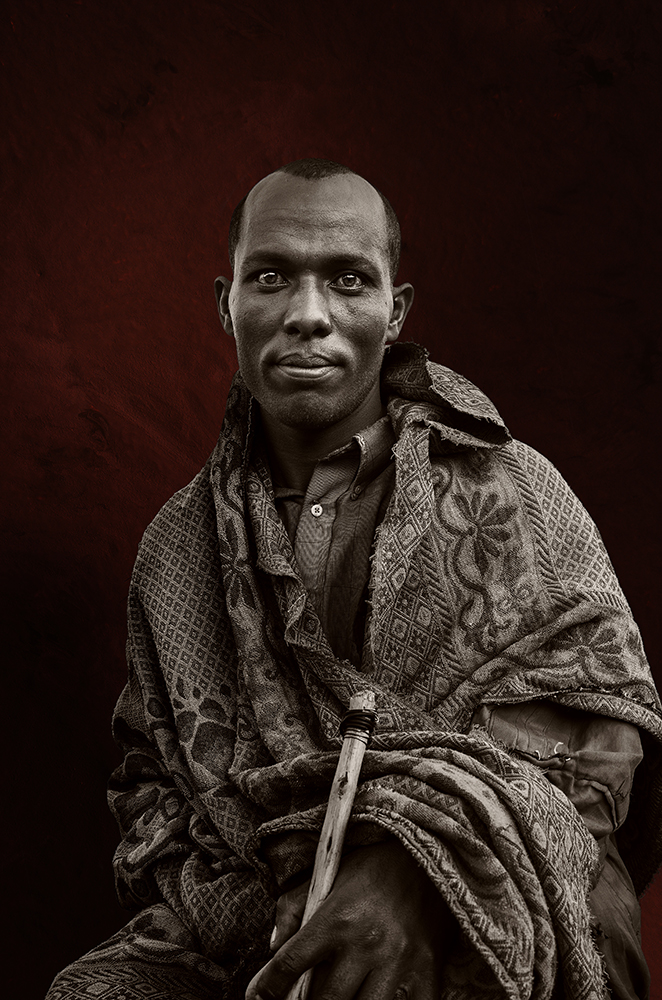

The purpose of this series of portraits is precisely that: the decontextualization, the elimination (as far as possible) of those clues that paradoxically take us away from the true essence of the model.

A decontextualization that initially throws us into uncertainty (where? when? how?) but that finally drives us to focus on the essence of the human being in front of us.

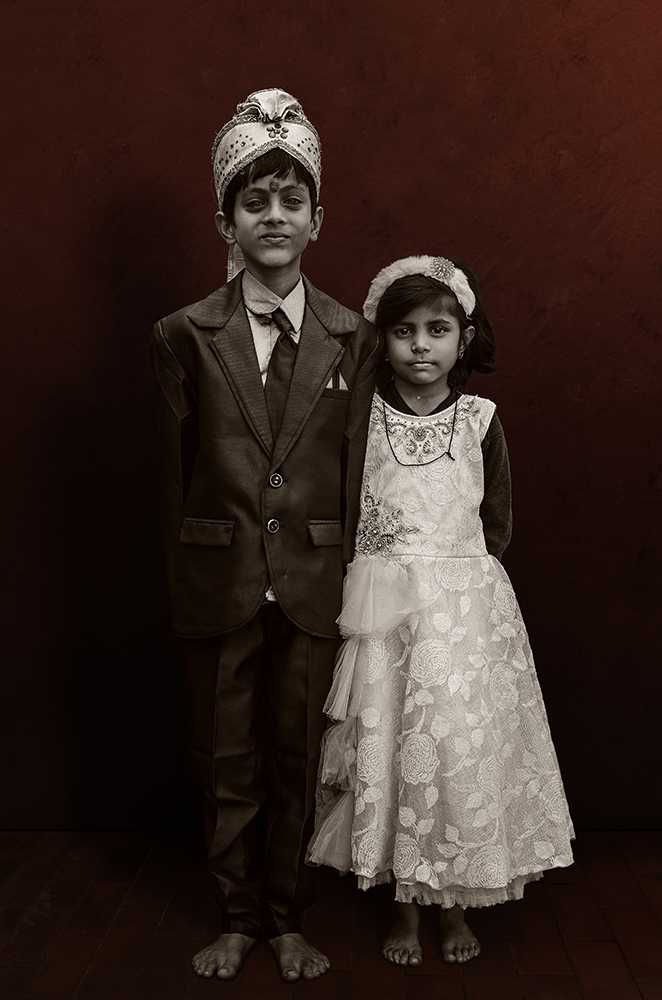

Certainly, some might say that it is impossible to completely eliminate all these visual clues. That's right, we can see a chador which quickly throws our imagination into the Muslim world. We can see too a rosary that informs us about the spirituality of the model. We can see children simply dressed for a party, but quickly the boy's traditional hat [called pagri] throws us back into the Hindu tradition. We can see orthodox crosses, facial paintings, strange hairstyles, or the certainty of having lived, as can be seen in the wrinkles of this old woman's face, etc., etc.

But none of that matters, I mean, I would like that none of that matters; on the contrary, I would like the viewer to focus on the fact that all of them, under the same red background that symbolizes the blood that flows through our veins and that makes us all absolutely equal, all of them I say, are staring at us, giving us back, like mirrors, the same questions we would like to ask them.

We tend to focus on the where, the when, and the how, and perhaps we should focus on the who. Certainly, we share neither country nor language nor religion, but the blood that flows through our veins has the same red color and that should be enough.

-In your opinion, how does the process of making and sharing art help bridge gaps in understanding among people from different backgrounds and experiences?

A Spanish philosopher said that the best vaccine against intolerance is to travel and get to know other cultures, to really get to know other ways of understanding the world. My photographs intend to do just that, to be windows to other worlds outside the viewer's world and to turn them into mirrors in which they can see themselves reflected.

-Do you have any experiences or encounters during your photographic journey that have left a lasting impact on you and influenced your artistic vision?

There has not been a single one of my photographic journeys/projects in which I have not returned with the firm conviction that all human beings yearn and suffer for the same things and have the same weaknesses and basenesses. I also believe, wherever you go, that closed social groups tend to be egocentric, tend to think that their own culture, their own beliefs, their social organization is the best of all. It is extraordinarily paradoxical that these patterns of intolerance and disdain for who/what is different are still reproduced in a hyper-connected world. I would like to believe that my work, in particular, and photography and art, in general, contribute to making a better world. All of these could be considerations that anyone can make, but in my case, I can say categorically that I owe them to photography.

-What’s the best way for someone to check out your work and provide support?

I don't believe much in social media. Like almost everything else in this world, they are at the service of those who create them, not those who use them, and they generate an artificially fast way of life.

I don't believe that seeing an image for just a couple of seconds has any positive and lasting effect on anyone.

What does a like mean? What does 100k likes mean? In my opinion, nothing, except for the one who receives them, if that is their only ambition, it's just smoke that vanishes as soon as you turn your head.

In my opinion, photography, like other forms of artistic expression, needs reflection; it needs time to ask questions and time to look for answers; none of that is possible if you can't sit in front of a photo printed on paper, be it a photo book or an exhibition and dedicate the necessary time to it. None of that is possible if your only access to a sculpture or a canvas is through a screen.

You need to smell and feel the work as it has been conceived.

It seems that these limits are still respected for painting, sculpture, and others, but for some reason, these limits have vanished for photography.

Whoever has never held a photograph on baryta paper in their hands, whoever has not experienced its touch and texture, will not understand what I am talking about.

That is my main aim regarding what would be the best way to make my work known, to reach people with time, the most precious but most despised object, and who are willing to ask themselves questions, who appreciate the pleasure of feeling and touching a photograph.

It is probably an ambitious, extemporaneous, and utopian goal in this day and age, but that is a risk one must be willing to take.

Statement

In a certain sense, the photographer's job is none other than to compose stories where the central character and various visual clues (social, economic, geographical...) weave a tapestry of sensations, of emotions, that give voice to that story.

However, these clues, on many occasions, turn against us, forcing a subtle and unconscious prejudice about what we contemplate.

The purpose of this series of portraits is precisely that: the decontextualization, the elimination (as far as possible) of those clues that paradoxically take us away from the true essence of the model. A decontextualization that initially throws us into uncertainty (where? when? how?) but that finally pushes us to focus on the essence of the human being in front of us.

From a strictly personal perspective , maybe we don't share a way of life, religion or country, but, no matter how much time has passed, they all accompany me wherever I am and, even though they are blurred by the passage of time, they populate my memories. Almost without realising it, they have ceased to be "the others"; they are something like my extended family.

In a world where Lampedusa, Catania, Puerto de los Cristianos, the Island of Lesbos and an innumerable list of places are ports of arrival, at best, for thousands and thousands of persons in search of a better life, it would be good, necessary and therapeutic to stop seeing migrants, to see simply and plainly persons.

We tend to focus on the where and the how, and perhaps we should focus our attention on the who?

Certainly, we share neither country nor language nor religion, but the blood that flows through our veins has the same red colour and that should be enough.

Bio

Born in Zamora, he currently lives in San Javier, Murcia, Spain. A retired secondary school technology teacher, he started in photography by building his own chemical developing laboratory 30 years ago, where he began to ask himself many questions about photography.

Rpnunyez thought that, with time, all these questions would be resolved, but far from it, a multitude of possible answers remain open.

He hardly photographs objects, which, if anything, are mere ornaments accompanying a single protagonist: the human being, with his strengths, miseries, longings and frustrations.

Rpnunyez confesses not to remember a single one of his photographs in which, at the moment of shooting, he was not accompanied by the deep conviction that only chance or even time is the only reason why he was not that old man from a remote tribe or that beggar sheltering from the rain under a piece of cardboard.

Rpnunyez does not photograph what he sees but what he is.

He never thinks of his photographs as art objects or objects of consumption, neither do they have anything to do with the ephemeral. He thinks of them as tools at the service of an idea as simple as it is masterfully summarized by Wayne Miller: to leave a testimony of the universal truths of the human being.

Having just finished his latest photographic project "SEMA The Ritual Dance of the Whirling Dervishes", he is currently working on his next project to document the lifestyle of Turkish society.